The EU-Africa Summit of 28 is imminent. This time around, Summit’s agenda is focused on youth but the elephant in the room will be migration.

Migration has to be part of the policies that the EU develops with and towards Africa. It is one of the great global issues of our time, and for two continents so close geographically there will always be complex patterns of two-way mobility, which are entangled with trade, development, and security policies. And the relationship between the two continents will always be tense due to money and history, inter alia, as a recent paper by International Crisis Group described well.

But a new risk to a constructive relationship – and to the wellbeing of the peoples of both continents – develops when Europe approaches migration from the narrow perspective of migration control, defined as prevention of migration from Africa to Europe, full stop.

Since “The Crisis” in too many debates on migration with EU policy-makers, particularly those representing Member States, the discussion rapidly descends into an ominous presentation of birth rates in Africa, with the implicit or explicit suggestion that ALL those as yet unborn Africans will “flood” to Europe. Rarely have demographic trends been so widely studied and cited or been framed in such a narrow and politically charged way. The broader reality of migration and Africa is simply disregarded.

First, most migration of Africans remains within Africa. Those routes across the Sahel lead people to other parts of their own continent, which is where most of them want to go. New research from Clingendael and from Oxfam shows that European efforts to disrupt migration also prevents regional migration and can have a negative economic impact.

Another fact so often disregarded is that many of the migrants arriving from Africa are refugees. The myth prevails that they are all economic migrants “clogging up asylum systems” (a charming expression that seems to be standard usage in DG Home). But there are enough countries in Africa where persecution by repressive regimes and conflict are common enough to mean many people arriving in Europe are entitled to protection.

At the same time, while the facts about the availability of black market work and about Europe’s aging population and the economic challenges it poses are often discussed in Africa, they seem rarely to feature in European decision making and debate. European policy-makers and civil society who try to inject these issues into discussion are shouted down as naïve or dangerous.

But things can be turned around. The African Union is becoming more engaged – it is currently developing its own position – and African civil society’s emerging activism on migration is welcome. Both have a stake in the politics of migration, most notably when Europeans’ panic leads to cooperation with corrupt, repressive or abusive regimes (also exacerbating the reasons why people want to leave).

In Africa the anger is palpable – and unsurprising. The openly racist rhetoric in Europe –from people who should know better as well as the extremists – is reported regularly, along with the stories of people drowning and search and rescue disrupted. For many, analysis of the news is coupled with wide knowledge of Europe’s historical and more recent involvement in generating the reasons for forced and voluntary migration: badly drawn borders that lead to conflict, support for repressive regimes, hosting of stolen assets, arms sales, etc. People in Africa think Europe has gone completely mad – with a political meltdown because of the arrival of manageable numbers of people, whom Europe needs.

We need above all joint work to fight the root causes of forced displacement. The good news is that we have 30+ years of evidence on what works in supporting development and preventing conflict. As well as reading scare stories about birth rates and assuming that every person born in Africa is heading to their house, European leaders would be better off reading some of this work. We need greater involvement of and resistance from development specialists, diplomats, trade officials and the security experts. These are the people who have experience in external affairs and in working with their African counterparts. It doesn’t make for good trade, development or security policy to focus on migration control (but yes, migration is part of all these policies).

The agenda has to be taken out of the hands of the internal affairs people with their migration control obsession and their narrow approach to security (hard borders – like that stops the real threats to Europeans’ security). And, by the way, tackling the “root causes of migration” does not mean paying a corrupt strongman wanted by the ICC to control borders.

For those who care about the future of EU external affairs, it is imperative to keep the broad and multi-faceted approach set out in the Global Strategy. An EU foreign policy that focuses purely on migration control is not serious (although it might suit some Member States). Often, the most useful thing that Europe could do is stop contributing to the causes of displacement. Oxfam’s report on the EU Trust Fund for Africa shows that it is funding good work in line with the SDG as well as problematic projects that are only about prevention of migration. The balance must shift to the former.

The other ways out of this situation are the legal migration routes that are gradually being opened. These are the safe and legal channels to safety for those who need protection and the multiple potential legal options for other forms of migration. African governments and civil society can insist on these positive elements being part of migration cooperation with Europe – the EU’s transactional approach provides them with leverage they can use. And why else should they support Europe’s agenda? The development money offered is in many cases not sufficient to replace the value of remittances provided by migrants.

Of course, there are countries which the EU should not be dealing with and governments it should not be reinforcing. In these cases, European civil society stands ready to work with our counterparts in Africa and with the relevant AU bodies to expose the human rights violations that result from migration control policy.

Some African countries are leading the way globally when it comes to protection of refugees through respect for their rights, such as their right to employment. Others are doing very badly, unable or unwilling to offer even basic protection. Many have a keen eye on developments in Europe. Supporting the rights of refugees in Africa is not an alternative to protection in Europe – it depends on it because if Europe gives it up, others will follow its lead. The migration piece is separate, involving different legal and practical measures. But both must involve getting people out of the hands of smugglers. Tackling the multiple reasons why they use smugglers is the way to do this, rather than supporting corruptible state institutions to tackle smugglers with one hand and take money from them with the other.

We are told that some of these options are “politically impossible”: unfortunately too much that was previously politically impossible or inconceivable (complicity with Libyan militias anyone?) is now happening. The reasonable and positive “impossibilities” should also be made possible through cross-sectoral and cross-continental alliances to resist the counter-productive agenda of migration control at any cost.

Catherine Woollard, ECRE Secretary General

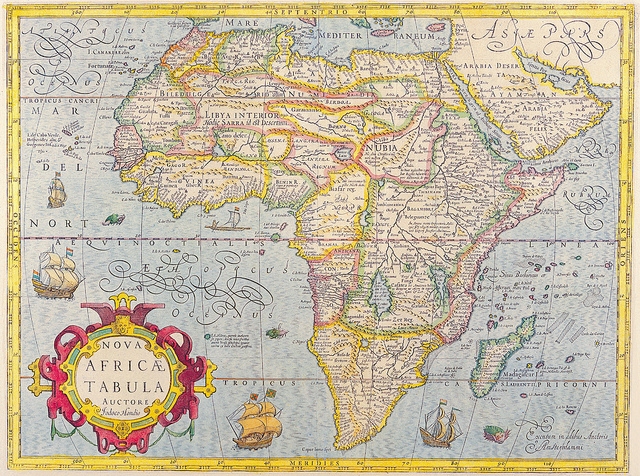

Photo: (cc) rosario fiore, September 2010