By Dr. Martin Lemberg-Pedersen, Assistant professor, Global Refugee Studies, Aalborg University

In 2015, the political meltdown that defined the European response to the global refugee crises, laid bare dilemmas long in the making. Since then, European citizens have heard their policy-makers talk of the need to “strengthen” the “soft” EU borders, and painting dystopian images of tsunamis of refugee-arrivals. This framing of the situation has been accompanied by a seemingly endless series of meetings and summits where European leaders discuss and celebrate a seemingly endless series of securitized initiatives. Libya is at the forefront of EU externalization efforts as a few examples will illustrate: on November 28, 2017, EU and Italy announced the allocation of €285 million to search and rescue centres in Libya, thus siding with one of several competing power bases in the country, the Tripoli-based government. This complemented an earlier EU-commitment of €46 million to two control facilities in Tripoli, operated by security forces.[i]

These initiatives, like many others, are now heralded as innovative game-changers by senior union officials, but are also fiercely criticized by human rights organizations. While evacuations are a humanitarian response to disastrous conditions, it is said, the systemic reasons behind these conditions, and the European responsibility for them, remain unaddressed. And crucially, the policy of partnering with Libya for migration control solutions, and the tragic consequences of such collaboration, is far from new.

The summer and fall of 2017 have offered terrible glimpses into the dehumanizing consequences of the externalization of migration control to Libyan territory. Images of abandoned corpses, young men offered on slave-markets, scars and fearful eyes telling tales of rampant beatings, abuse and torture and women traded for systematic rape in camps designed for the same purpose have created shock in the European and global public.[ii] Newspapers and documentaries have picked up the stories from the racialized hierarchies of the Libyan migration system leading the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi to call the conditions an “abomination”.[iii]

Externalization works through a preventive rationale, whereby the arrival of people to European territory is preempted, so that the rights of people to access asylum procedures is negated before they can reach the territory where it is activated. But the European narratives justifying this policy have moved uncomfortably between two extremes: On the one hand, the externalized control is presented as a catalyst for human rights through partnerships based on rule of law and international obligations. On the other hand, deals like the one between EU and Turkey, or with questionable Libyan actors are also presented as a harsh, but necessary bulwark against a tide of smugglers and immigrants.

The European shock associated with the consequences of the Libyan migration system is therefore paradoxical. It has been both ignored and acknowledged for years. Constantly framed as a new and innovative approach to migration, the policy has been underway for around two decades. Explicitly pursued when communicating to certain voter segments, but disavowed and denied when communicating to others. In a similar manner, today, the militarized Operation Sophia between Libya and Italy is both heralded as saving migrants, is predicted to have collateral damage for refugees and other civilians, and as cracking down on smuggling networks, migrants´ only means of escaping Libya given the European closure of legal mobility channels.

Bilateral Italian-Libyan relations constituted a forerunner for the current Libya policy, but common-European efforts have actually existed for a long time. In 2002, for instance, the Danish EU-presidency stated that cooperation on migration control with Libya was “essential”, the 2004 and 2007 Technical Missions to Libya by, respectively, the EU Commission and Frontex did the same, and, all but bypassing the massive rights violations taking place, and Libya´s refusal to sign the 1951 Refugee Convention, recommended supporting an expansion of Libyan border security and police forces. Similarly, the 2008 Italian-Libyan agreement, framed by Gaddafi and Berlusconi as a apology from Italy to its former colony, actually constituted the postcolonial continuation of the relation, launching push back-operations whereby migrants where returned by Italian vessels to the inhumane and degrading conditions in Libyan camps and prisons. Externalization to Libya has been a central EU policy for more than a decade.

When some European officials and politicians are confronted with the growing body of reports, media- and witness-accounts of the brutal consequences of the policy, they voice despair with the rivalling Tripoli and Tobruk-governments, and express a certain longing for the days when Gaddafi was in power. The strong man could guarantee the closing of borders by cracking fiercely down on the desperate people trapped in his EU-supported control system. But, this memory offers only a false sense of security, conveniently forgetting how Gaddafi repeatedly used Europe´s fear of immigration as a bargaining chip to extract influence and power. Just like Recep Tayyip Erdogan is doing now. Besides the grave humanitarian risks associated with stable externalization partners like Gaddafi, there are also serious political risks attached to the policy.

Moreover, already in Gaddafi´s era, the police, military and smuggling sectors were thoroughly interconnected, to the point that many migrants could not distinguish between the actors who were all kidnapping, brutalizing and robbing them.[iv] This is one reason why the political focus on combating smugglers is problematic. Another is the fact that the need for smugglers´ service is inversely proportional to the lack of legal escape or labor routes. As European border control has expanded since the 2000s, so has the smuggling industry.

The fact that Europe is still in search of a solution to migrants crossing the Central Mediterranean therefore indicate that European leaders have spent far too much time focusing on avoiding the arrival of refugees and migrants, and far too little on determining what to do when displacement occurs and people manage to arrive.

This was illustrated when, in 2015, after decades of EU border control policy-making, only half a year of rising asylum numbers (at levels much lower than the biggest refugee-hosting countries around the world), led to the fragmentation of the EU, and an unprecedented crisis of authority for the Commission. Two and half year on, the non-compliance of several member states, has meant that even the extremely modest goals for resettlement and relocation of refugees set in 2015 have failed. The year-long unwillingness of most member states to reconsider the unfair EU border system, left the union ill-equipped to react when an actual, even if modest on a global scale, displacement crisis emerged from 2013 and onwards.

Externalization, constitutes a route to building consensus in troubled European waters. The partnerships with Europe´s neighbors illustrate that displacement appears to enter the realm of serious political issues only when it involves European territory. This means that many European political discussions of displacement treat the original causes for displacement as inevitable, appearing out of nowhere. This, however, fails to account for their inherently political nature including that, for many displacement crises, these facts are causally linked to a range of Europe´s own policies, like conflicts, resource- and mineral extraction, arms export, labor and trade policy, over-fisheries, land- and water-grabbing and collusion with corrupt regimes. Focusing only on border-crossings via externalization and the fight against smugglers is[v] therefore just palliative approaches.

We may ask why this approach then continues, and even experiences growing political popularity. When it comes to control collusion with countries like Libya, part of the reason is that, just like the root causes of displacement, the policy is linked with lucrative export markets.[vi] For some years, border control infrastructures have been an emerging and highly profitable market for Italian, French, German, British and Danish arms, security and IT-companies.[vii] Control equipment totaling billions of Euro have been exported to countries like Turkey, Libya, Niger, Chad, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Turkey and Sudan in tune with European visions from the 1980s of concentric circles of flanking measures protecting the union´s self-identified area of freedom, security and justice.

When it comes to the externalization partners, the European policy also creates a vicious cycle since the influx of arms and funds to the kind of actors willing to enact the European agenda of preemptive control, means that more democratic, transparent and sustainable actors unwilling to act as Europe´s buffer and incarceration zones are politically and economically undermined. By contrast, the policy emboldens actors like the Libyan Brigade 48 or the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces[vii] (formerly known as Janjaweed) who vie for legitimacy by inserting themselves into power vacuums, asking for recognition, and financial compensation, for their preemptive migration control.[ix] In this manner, the pursuit of the short-term goal of preventing immigration has the effect of undermining the long-term goal of tackling the root causes of displacement.

Different from Europe´s collusion with Gaddafi, the abject horrors in the Libyan migration system are now highly mediatized, and out there to be seen. Yet, instead of using the current moment of low arrival numbers to construct a more sustainable, humane and fair border system, short-term policies fusing containment and humanitarianism outside Europe are experiencing a political renaissance. And efforts are underway to export migration control to even more actors: The French spearhead the expansion of the G5 Sahel Force´s mandate to migration control and Germany has initiated a similar development with the Khartoum Process targeting actors in the Horn of Africa.[x] These represent the worrying prospect that migration control is increasingly being pushed into the very regions generating displacement.

ECRE publishes op-eds by commentators with relevant experience and expertise in the field who want to contribute to the debate on refugee rights in Europe. The views expressed are those of the author and does not necessarily reflect ECRE positions

[i] https://euobserver.com/migration/140067

[ii] http://edition.cnn.com/videos/world/2017/11/13/libya-migrant-slave-auction-lon-orig-md-ejk.cnn

[iii] https://reliefweb.int/report/libya/high-commissioner-refugees-calls-slavery-other-abuses-libya-abomination-can-no-longer

[iv] https://www.euractiv.com/section/justice-home-affairs/news/erdogan-threatened-to-flood-europe-with-refugees/

[v] https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/italy0909web_0.pdf

[vi] https://www.tni.org/en/publication/border-wars

[vii] https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2015/10/unravelling

[viii] https://enoughproject.org/reports/border-control-hell-how-eus-migration-partnership-legitimizes-sudans-militia-stat

[ix] http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/libyan-militias-being-bribed-stop-migrants-crossing-europe-2107168893

[x] http://www.statewatch.org/news/2015/oct/khartoum-process.htm

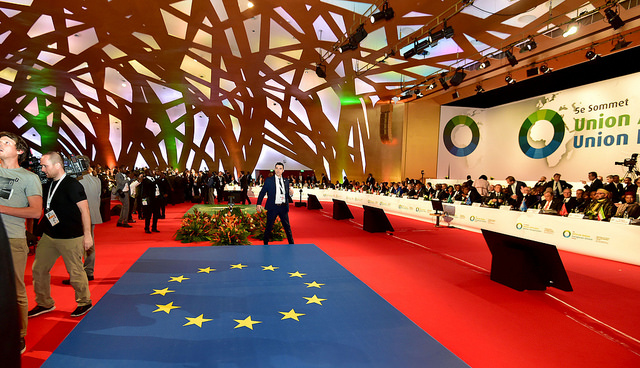

Photo: (cc) GovernmentZA, November 2017